A pre-money valuation is what a company is believed to be worth prior to raising a priced round of equity financing. John Rikhtegar, Vice President, Growth Capital, RBCx Capital, shares insights on how a valuation is determined and why you may need one.

As any startup founder will attest, leading a business from idea to exit has its share of twists and turns. From developing the product, to building a team, to navigating the market, founders aim to hit performance milestones to ensure their fledgling startup remains capable of developing into an established enterprise. Amid a business lifecycle predicated on continuous change, pressure to scale, and ensuing cashburn (that’s become normalized in tech), knowing the value of your company can be a challenge. When the time comes to seek startup funding, however, a pre-money valuation becomes a necessity.

Much like the startup journey itself, the valuation of an early stage venture is rarely straightforward. John Rikhtegar, Vice President, Growth Capital, RBCx Capital, shares his insights on valuations. John supports early stage clients across capital fundraising and strategic growth, and leads direct, indirect, and strategic investment opportunities. To help first-time founders become familiar with the process of pre-money valuations, this article covers:

What is a pre-money valuation?

Why is a pre-money valuation important?

Methods to determine a valuation

Limitations of a private valuation

Why a higher valuation isn’t always better

“Pre-money valuations form the basis for all VC negotiations as it influences a company’s price per share, the number of new shares required in a financing round, and the ultimate ownership stake an investor will hold based on their investment.”

What’s a pre-money valuation?

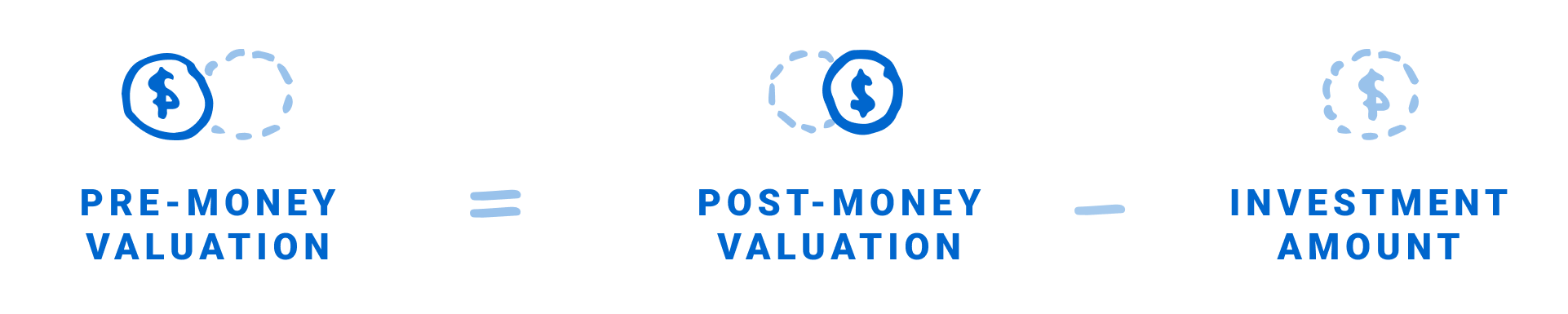

A pre-money valuation is what a company is believed to be worth prior to raising a priced round of equity financing. This valuation is necessary to determine the share of equity that investors will receive in exchange for the capital they provide. A post-money valuation, on the other hand, is the projected value of the company after the financing round has been completed.

A valuation, in essence, is a price of an asset—the perceived value or worth of a company, typically as determined by the company, its investors, prospective investors, and external market players (i.e. analysts). The valuation usually establishes how much the company and its investors value the company at a specific point in time.

“Pre-money valuations form the basis for all VC negotiations as it influences a company’s price per share, the number of new shares required in a financing round, and the ultimate ownership stake an investor will hold based on their investment,” says John.

How do you calculate pre-money valuation?

The pre-money valuation is calculated as the post-money valuation minus the additional capital raised during the priced round of equity financing.

Pre-money valuation example

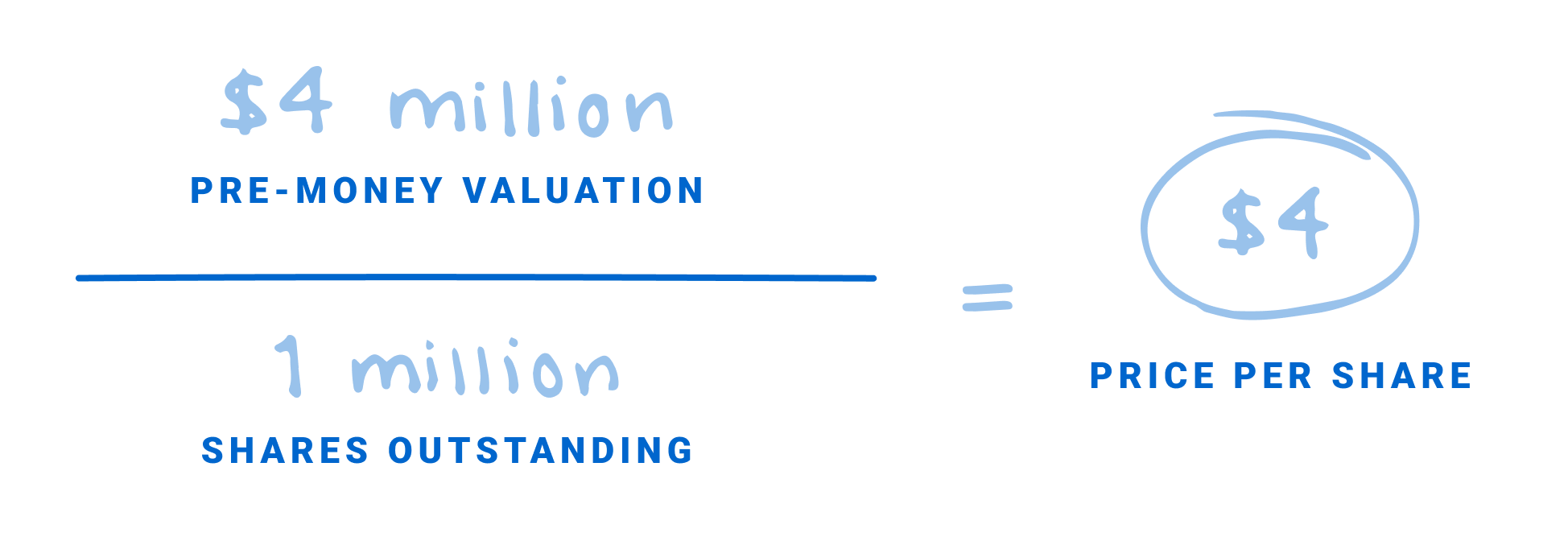

Founder, Anika, owns 100 per cent of her business and has 1 million shares outstanding. She is looking to raise capital for her startup and plans to raise $1 million on a $4 million pre-money valuation. Therefore, the implied price per share of her company is worth $4.

To raise her target of $1 million, she needs to issue an additional 250,000 shares.

$4 price per share x 250,000 shares = $1 million

Anika will give up 20 per cent ownership in her company for $1 million in equity financing.

| Amount | Shares | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Founder | $4,000,000 | 1 million | 80% |

| Investor | $1,000,000 | 250,000 | 20% |

| Total | $5,000,000 | 1.25 million | 100% |

Preferred shares help mitigate investors’ risk

Preferred (“Pref”) shares are typically offered to investors in private company financings. They form the basis of their shareholder’s equity post-investment as these shares include benefits over common shares typically held by founders, employees, and few potential early stage investors. Preferred shares include a liquidation preference, participation right, and anti-dilution rights. These benefits help mitigate the investors’ risk and are typically provided to safeguard against overvaluation. Even though various analytical techniques are used in its assessment, a company’s pre-money valuation is open to interpretation.

“Investors bear the equity risk involved in a private company financing,” says John. “Their investment, although theoretically may have infinite upside, has capped downside of going down to zero. Stated otherwise, an investor could make over 100 times (100x) their money if their initial start-up investment became the next Google or Microsoft.” But conversely, if it went bankrupt, an investor could only ever lose 1x their money (i.e. the original investment).

“ The ‘asymmetry to the upside’ is what makes venture capital such an attractive asset class to various investors,” John says.

A pre-money valuation is not permanent

A pre-money valuation is set at a definitive point in time and is subject to change as the company matures and scales its operations.

For example:

A company that raised $4 million on a $12 million pre-money ($16 million post-money), may look to hit the fundraising trail once again 18 months later, and set their new pre-money at $30 million given the maturation and strong traction the business has secured since their last priced equity round.

Though our technology ecosystem is accustomed to these ‘up-rounds’ as companies raised more and more capital, we are about to enter a period of unfamiliar territory, as founders are forced to raise capital at a ‘down-round’. A down-round occurs when the pre-money valuation of a company’s current round is less than the post-money valuation of a company’s previous round.

Using the example above, if the company is currently raising on a $12 million pre-money (rather than $30 million), this will be raising at a down-round because it’s lower than the $16 million post-money of its previous round.

Why is a pre-money valuation important?

As companies aim to build through the ‘valley of death’ where revenues are low and relative expenses are high, startups must secure external sources of capital to finance early company operations. In technology, most startups turn to VCs to secure that capital whereby equity capital is typically provided in exchange for company ownership (though not exclusively, as investors may choose to provide convertible debt instead).

“Valuations are used as the market clearing price for an asset and form the basis for enabling buyers and sellers to complete transactions.”

A pre-money valuation is a prerequisite to completing a formal priced round of equity financing. It provides investors with a basis for determining the current equity ownership of existing shareholders—does an investor own 20 per cent of a $2 million or a $20 million business? A pre-money valuation also determines the value of each share to be sold to new investors. This can be used to calculate how many shares need to be issued based on the pre-money price and capital injection targeted (as conveyed in the example with Anika).

“Taking a step back, a valuation is essentially a price for what a group of individuals believe an asset to be worth,” says John. “That asset, theoretically, can be a can of pop showing a price of $1.50 on the shelf of your local bodega, or a late-stage software business worth $250 million. Valuations are used as the market clearing price for an asset and form the basis for enabling buyers and sellers to complete transactions.”

Current investors need to understand how much their ownership in an asset is worth. For new investors, the valuation illuminates how much a prospective asset is priced to inform their interest in purchasing it. A pre-money valuation is also useful for founders and employees, as it offers a more objective lens on how much their business is worth—and its overall attractiveness—to investors.

Methods to determine pre-money valuations

The methods used for startup valuations are highly dependent on the stage of the company and the transaction. An early stage startup valuation will be based on a more qualitative set of investment heuristics. For investors of early stage companies with minimal traction (that may even be pre-product), the key areas they consider to set the valuation are:

- Calibre of founding team

- Business model and anticipated capital requirements (i.e. B2C vs. B2B models)

- External references and due diligence on independent market validation

- Use of proceeds in meeting desired target milestones

- Validity, size, and expected growth of the total addressable market.

VCs will want to assess market attractiveness (whether it’s health care, enterprise software, micro-mobility or other) to ensure the market that the startup is building in is large in size, and:

- There are no regulatory barriers/roadblocks

- There is strong anticipated market growth

- There has already been strong growth over the previous few years

- Is not overheated, crowded, or hyper-competitive.

Conversely, a late-stage, mature startup with more data available from company operations will be analyzed through a more rigorous quantitative and qualitative assessment.

“For mid-to-late stage companies, sample quantitative heuristics, both historical and forecasted, used to assess an appropriate company valuation may include revenue growth rates, net new ARR added per quarter, cash conversion rate, burn multiple, net revenue retention or churn rates, and company headcount growth,” says John.

In later stage transactions, investors use a more formal set of tools to value a company. Two common methods are discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis and multiple analysis.

What is a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis?

The DCF analysis is based on the future cash flows of a company, which is then discounted back to the present-day value to build an implicit Net Present Value (NPV). An investor can then use the NPV as a starting point to price an asset and align their target return expectations with a fair company valuation.

“Though this intuitively makes sense,” John says, the DCF method “has historically been less valuable in technology companies’ valuations as they have typically been cash-burning and pre-profit enterprises growing topline revenue at the expense of short to mid-term profitability.” He adds, this is why a private technology company valuation has been traditionally more heavily indexed in public market comparables and focused on top-line revenue metrics.

What is a multiple or comparable analysis?

A more common tool for valuing growth stage businesses is the multiple or comparable analysis. This method allows investors to benchmark a company to other private and public holdings, and thus determine how its perceived valuation is justified against peers. “Though multiple analysis is not perfect, it is one tool that investors have in aiming to assess a company’s valuation through a more objective and competitive lens,” says John.

A common metric used to value software businesses is the multiple of ARR (annual recurring revenue) or EV/NTM (enterprise value to next twelve months) revenue multiple. This was adopted because most SaaS businesses are billed through monthly or annual subscriptions which can make revenue forecasts highly predictable, while assuming a given level of churn.

“Traditionally, we have seen that the faster the growth in a given company, the higher the multiple EV/NTM (enterprise value to next twelve months) investors are willing to pay for that business.”

“Traditionally, we have seen that the faster the growth in a given company, the higher the EV/NTM multiple investors are willing to pay for that business,” says John.

For example, a business generating $10 million in revenue, valued at a 10x multiple would hold a valuation of $100 million.

If that business is assumed to grow 100 per cent year-over-year for the subsequent two years, investors would only be theoretically paying a 5x multiple next year and a 2.5x multiple the following year:

Year 1

$10 million x 100% growth = $20 million / $100 million valuation

= 0.5 or 5x multiple

Year 2

$20 million x 100% growth = $40 million / $100 million

= 0.25 or 2.5x

“That would be the opposite for lower growth businesses, as they would not be justified with a similarly high valuation,” explains John. “This is a core reason why investors have heavily prioritized a growth-first philosophy in technology investing.”

Who determines the valuation of a company?

A valuation of a company is ultimately decided upon by both the buyer (investor) and seller (founder) to complete a financing transaction. When completing a private financing round, there is one lead investor (or a few, in some instances) that leads the negotiations with the company on the terms and valuation of the investment, identifies and recruits other investors to participate in the round, and ultimately closes the deal.

Though all investors (to some degree) will perform their own due diligence and valuation analysis on the company, “the lead investor is ultimately the one that sets the valuation of the company for investors to pile in on,” says John.

What are the limitations of a private valuation?

Valuations on businesses in the private markets are not ‘marked-to-market’ like companies in the public market. While the valuation of a publicly traded company is updated in real-time, private market valuations are not updated as often as they should to reflect the true current business value.

“A company that raised capital two years ago at a $100 million valuation may still hold that valuation today simply because they have not undergone an independent valuation process since, nor completed a subsequent priced equity round. The valuation, therefore, does not reflect the current company’s state,” says John. “It may have grown significantly and worth much more than $100 million or, conversely, it may have experienced little growth and is worth much less. This makes private market benchmarking and VC portfolio evaluation a very interesting process.”

With incentives aligned for founders and investors to raise more capital on higher valuations, the valuation setting process has become more difficult to navigate.

Over the previous years, the private equity market has received strong macroeconomic tailwinds by way of record low inflation and interest rates, along with a strong performing public market landscape. Founders and investors pushed for higher valuations across each financing round and these incentives made some companies appear more valuable than what they were.

Is a higher valuation always better?

Advantages of high valuations

As companies take on higher valuations, there are some advantages for both founders and investors:

- Founders get diluted less on a higher relative valuation (they own a greater share of a more valuable company).

- Companies can raise more capital for the same level of dilution (i.e. a 20 per cent dilution on a $25 million valuation versus a $50 million valuation is the difference between $5 million and $10 million).

- More capital can typically correlate with a longer runway, meaning companies don’t have to hit the fundraising trail again.

- Higher subsequent valuations means VC portfolios are being marked upwards and they are showing strong paper returns to their investor base (otherwise known as limited partners).

Disadvantages of high valuations

There are also disadvantages to taking on too high a valuation:

- Companies can get too reliant on perpetually raising more and more capital, and when capital is no longer available (like what’s happening in today’s market), these companies become vulnerable.

- As founders become more reliant on capital, they may be more vulnerable to higher dilution over the longer term from raising more rounds of financings—some with potential downside protection.

- The exit path shrinks for businesses with higher valuations, as there are only so many avenues to exit a $1 billion business vs. a $100 million business.

- Investor expectations are increased, and founder stress follows suit, as the bar to justify hitting the next valuation is incredibly high.

The pre-money valuation of a startup is an essential step to acquire venture capital, and understanding the process can help ensure both the investor and founder reach a mutually beneficial arrangement. RBCx offers support to early stage clients across capital fundraising and strategic growth. We back some of Canada’s most daring tech companies and idea generators, turning our experience, networks, and capital into your competitive advantage to help drive lasting change. Speak with a RBCx Technology Advisor to learn more about how we can help your business grow.